Population ecology

Population ecology is a major sub-field of ecology that deals with the dynamics of species populations and how these populations interact with the environment.[1]

The first journal publication of the Society of Population Ecology, titled Population Ecology (originally called Researches on Population Ecology), was released in 1952.[1] Population ecology is concerned with the study of groups of organisms that live together in time and space. One of the first laws of population ecology is the Thomas Malthus' exponential law of population growth.[2] This law states that:

"...a population will grow (or decline) exponentially as long as the environment experienced by all individuals in the population remains constant."[2]:18

At its most elementary level, interspecific competition involves two species utilizing a similar resource. It rapidly gets more complicated, but stripping the phenomenon of all its complications, this is the basic principal: two consumers consuming the same resource.[3]:222

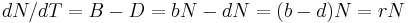

This premise in population ecology provides the basis for formulating predictive theories and tests that follow. Simplified population models usually start with four key variables including death, birth, immigration, and emigration. Mathematical models used to calculate changes in population demographics and evolution hold the assumption (or null hypothesis) of no external influence. Models can be more mathematically complex where "...several competing hypotheses are simultaneously confronted with the data."[4] For example, in a closed system where immigration and emigration does not take place, the per capita rates of change in a population can be described as:

,

,

where N is the total number of individuals in the population, B is the number of births, D is the number of deaths, b and d are the per capita rates of birth and death respectively, and r is the per capita rate of population change. This formula can be read as the rate of change in the population (dN/dT) is equal to births minus deaths (B - D).[2][3]

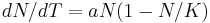

Using these techniques, Malthus' population principal of growth was later transformed into a mathematical model known as the logistic equation:

,

,

where N is the biomass density, a is the maximum per-capita rate of change, and K is the carrying capacity of the population. The formula can be read as follows, the rate of change in the population (dN/dT) is equal to growth (aN) that is limited by carrying capacity (1-N/K). From these basic mathematical principals the discipline of population ecology expands into a field of investigation that queries the demographics of real populations and tests these results against the statistical models. The field of population ecology often uses data on life history and matrix algebra to develop projection matrices on fecundity and survivorship. This information is used for managing wildlife stocks and setting harvest quotas [3][5]

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Species population | All individuals of a species. |

| Metapopulation | A set of spatially disjunct populations, among which there is some immigration. |

| Population | A group of conspecific individuals that is demographically, genetically, or spatially disjunct from other groups of individuals. |

| Aggregation | A spatially clustered group of individuals. |

| Deme | A group of individuals more genetically similar to each other than to other individuals, usually with some degree of spatial isolation as well. |

| Local population | A group of individuals within an investigator-delimited area smaller than the geographic range of the species and often within a population (as defined above). A local population could be a disjunct population as well. |

| Subpopulation | An arbitrary spatially-delimited subset of individuals from within a population (as defined above). |

An important concept in population ecology is the r/K selection theory. The first variable is r (the intrinsic rate of natural increase in population size, density independent) and the second variable is K (the carrying capacity of a population, density dependent).[7] An r-selected species (e.g., many kinds of insects, such as aphids[8]) is one that has high rates of fecundity, low levels of parental investment in the young, and high rates of mortality before individuals reach maturity. Evolution favors productivity in r-selected species. In contrast, a K-selected species (such as humans) has low rates of fecundity, high levels of parental investment in the young, and low rates of mortality as individuals mature. Evolution in K-selected species favors efficiency in the conversion of more resources into fewer offspring.[9][10]

Populations are also studied and conceptualized through the metapopulation concept. The metapopulation concept was introduced in 1969[11]:

"as a population of populations which go extinct locally and recolonize."[12]:105

Metapopulation ecology is a simplified model of the landscape into patches of varying levels of quality.[13] Patches are either occupied or they are not. Migrants moving among the patches are structured into metapopulations either as sources or sinks. Source patches are productive sites that generate a seasonal supply of migrants to other patch locations. Sink patches are unproductive sites that only receive migrants. In metapopulation terminology there are emigrants (individuals that leave a patch) and immigrants (individuals that move into a patch). Metapopulation models examine patch dynamics over time to answer questions about spatial and demographic ecology. An important concept in metapopulation ecology is the rescue effect, where small patches of lower quality (i.e., sinks) are maintained by a seasonal influx of new immigrants. Metapopulation structure evolves from year to year, where some patches are sinks, such as dry years, and become sources when conditions are more favorable. Ecologists utilize a mixture of computer models and field studies to explain metapopulation structure.[14]

The older term, autecology (from Greek: αὐτο, auto, "self"; οίκος, oikos, "household"; and λόγος, logos, "knowledge") refers to roughly the same field of study, coming from the division of ecology into autecology—the study of individual species in relation to the environment—and synecology—the study of groups of organisms in relation to the environment—or community ecology. Odum (1959, p. 8) considered that synecology should be divided into population ecology, community ecology, and ecosystem ecology, defining autecology as essentially "species ecology."[1] However, for some time biologists have recognized that the more significant level of organization of a species is a population, because at this level the species gene pool is most coherent. In fact, Odum regarded "autecology" as no longer a "present tendency" in ecology (i.e., an archaic term), although included "species ecology"—studies emphasizing life history and behavior as adaptations to the environment of individual organisms or species—as one of four sub-divisions of ecology.

The development of the field of population ecology owes much to the science of demography and the use of actuarial life tables. Population ecology has also played an important role in the development of the field of conservation biology especially in the development of population viability analysis (PVA) which makes it possible to predict the long-term probability of a species persisting in a given habitat patch (e.g., a national park).

While essentially a subfield of biology, population ecology provides many interesting problems for mathematicians and statisticians, who work mainly in the study of population dynamics.

Contents |

Scientific literature

Scientific literature on population ecology can be found in The Journal of Animal Ecology, Oikos and other journals.

See also

- Density-dependent inhibition

- Genetic variation

- Irruptive growth

- Life table

- Malthusian growth model

- Metapopulation

- Overpopulation

- Overpopulation in companion animals

- Population density

- Population distribution

- Population dynamics

- Population genetics

- Population growth

- Population size

- Important publications in autecology

- Reproduction

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Odum, Eugene P. (1959). Fundamentals of Ecology (Second ed.). Philadelphia and London: W. B. Saunders Co.. p. 546 p. ISBN 0721669417/9780721669410. OCLC 554879.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Turchin, P. (2001), "Does Population Ecology Have General Laws?", Oikos 94 (1): 17–26

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Vandermeer, J. H.; Goldberg, D. E. (2003), Population ecology: First principles, Woodstock, Oxfordshire: Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-11440-4

- ↑ Johnson, J. B.; Omland, K. S. (2004), "Model selection in ecology and evolution.", Trends in Ecology and Evolution 19 (2): 101–108, http://www.usm.maine.edu/bio/courses/bio621/model_selection.pdf

- ↑ Berryman, A. A. (1992). "The Origins and Evolution of Predator-Prey Theory". Ecology 73 (5): 1530–1535.

- ↑ Terms and definitions directly quoted from: Wells, J. V.; Richmond, M. E. (1995). "Populations, metapopulations, and species populations: What are they and who should care?". Wildlife Society Bulletin 23 (3): 458–462. http://www.uoguelph.ca/zoology/courses/BIOL3130/wells11.pdf.

- ↑ Begon, M.; Townsend, C. R.; Harper, J. L. (2006), Ecology: From Individuals to Ecosystems (4th ed.), Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing, ISBN 978-1-4051-1117-1, http://books.google.ca/books?id=Lsf1lkYKoHEC&printsec=frontcover&dq=ecology&lr=&as_drrb_is=b&as_minm_is=0&as_miny_is=2004&as_maxm_is=0&as_maxy_is=2009&as_brr=0&client=firefox-a&cd=1#v=onepage&q=&f=false

- ↑ Whitham, T. G. (1978). "Habitat Selection by Pemphigus Aphids in Response to Response Limitation and Competition". Ecology 59 (6): 1164–1176.

- ↑ MacArthur, R.; Wilson, E. O. (1967), The Theory of Island Biogeography, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press

- ↑ Pianka, E. R. (1972). "r and K Selection or b and d Selection?". The American Naturalist 106 (951): 581–588.

- ↑ Levins, R. (1969). "Some demographic and genetic consequences of environmental heterogeneity for biological control.". Bulletin of the Entomological Society of America 15: 237–240. http://books.google.ca/books?hl=en&lr=&id=8jfmor8wVG4C&oi=fnd&pg=PA162&ots=GJCtM8hhbu&sig=kSiFKPIaX_p_ZCeQZtf1G0k4ib4#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

- ↑ Levins, R. (1970). Gerstenhaber, M.. ed. Extinction. In: Some Mathematical Questions in Biology. pp. 77–107. http://books.google.ca/books?id=CfZHU1aZqJsC&dq=Some+Mathematical+Questions+in+Biology&printsec=frontcover&source=bl&ots=UXQZc5WZwK&sig=1F6yBuo09HOAwxFL5QA8Ak_BLA0&hl=en&ei=V2U9S5SyLpDflAe40qmdBw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CAwQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

- ↑ Hanski, I. (1998). "Metapopulation dynamics". Nature 396: 41–49. http://www.helsinki.fi/~ihanski/Articles/Nature%201998%20Hanski.pdf.

- ↑ Hanski, I.; Gaggiotti, O. E., eds (2004). Ecology, genetics and evolution of metapopulations.. Burlington, MA: Elsevier Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-323448-4. http://books.google.ca/books?id=EP8TAQAAIAAJ&q=ecology,+genetics,+and+evolution+of+metapopulations&dq=ecology,+genetics,+and+evolution+of+metapopulations&cd=1.

Further reading

- Kareiva, Peter (1989). "Renewing the Dialogue between Theory and Experiments in Population Ecology". In Roughgarden J., R.M. May and S. A. Levin. Perspectives in ecological theory. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 394 p.

- Odum, Eugene P. (1959). Fundamentals of Ecology (Second ed.). Philadelphia and London: W. B. Saunders Co.. p. 546 p. ISBN 0721669417/9780721669410. OCLC 554879.

- Smith, Frederick E. (1952). "Experimental methods in population dynamics: a critique". Ecology 33: 441–450. doi:10.2307/1931519.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||